I just came across a recent book on the history of photographic printing, Richard Benson's The Printed Picture (2008). It was produced in conjunction with an exhibit at MoMA in New York and reads something like an exhibition catalog. It covers the history of photographic processes and print reproduction briefly and in a non-technical way. It's thin on detail but good for a quick 10,000-foot view.

It was interesting to see how high quality printing of images has been possible for a long time through processes like photogravure and collotype. These are expensive and comparatively fussy processes that have been mostly supplanted (or entirely for collotype) by offset printing, even for high quality reproduction. And with good reason. Quality offset printing is really superb.

The main issue for most publications is, of course, cost. Producing great printing for $100 art books is one thing, but doing it for a $2 magazine is another. Two mass-market publications often praised for their printing quality are Arizona Highways and National Geographic. Arizona Highways prints at 175 lpi using standard offset color. It looks good for a $2 magazine, certainly, though what is a little surprising is that almost any well-produced magazine today looks equally good next to it.

Benson is unabashedly enthusiastic about offset printing, "my trade and my chief love." "Today," he says, "we are witnessing the peak of the process's development. . . . I think it will be around for quite a while yet." While a $2 offset-printed magazine can look quite good, Aperture and some other art-grade periodicals reveal that a $10 offset color journal can achieve near-photo-print quality.

National Geographic has long used 175 lpi (perhaps higher for some plates) six-color rotogravure rather than offset for its editorial well content. Gravure uses regular square cells etched to different depths, each cell being inked to a different depth to describe tones, rather than using dots of varying sizes like offset. This can produce images that look much more like photographic prints. Gravure was the high standard for photo printing in books and journals from the turn of the century though the 1960s. At its apogee, in the hands of the Swiss and French in the 50s and 60s, "the printing is among the very best ever done."

The superlative flat-plate gravure of these old photo books is long gone. National Geographic's modern web-press gravure process is, comparatively, a poor cousin, but at its best is still as good as you can get in a $2 magazine. This expensive process is only cost effective for them because they print six million copies of every issue. Ten years ago that was almost nine million, and with a shrinking subscriber base, it seems their print quality has dropped a bit, too. Issues from the 1990s used a slightly heavier stock and on average exhibited less streaking, skip dot and dirty scrape. Some people attribute this to a change of printer (Quad/Graphics) about ten years ago.

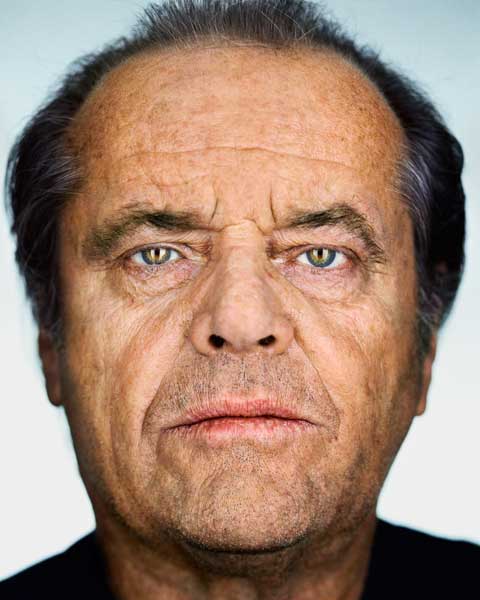

"Despite its complexity," says Benson,"in the end color printing turned out to be easier to do well than black and white." The reasons for this are bit complex and obscure, but basically, color printing "could be done badly and still look good. Even if the print was too heavy, or too light, or somewhat out of balance, the colors' interrelationships could still hold and the colors could be enticing, even if inaccurate. . . . But in black and white work, errors in weight and scale could remove whole areas of content, and tonal distortions could murder the picture."

Just as print starts to fade and ebooks begin to dominate, I find myself becoming increasingly compelled by fine printing. Fortunately, I believe the most aesthetic books with be the last to disappear. They are more than carriers of information and will long have an audience. And on the art side, printed books have never been more beautiful or inexpensive. Print may be tipping into decline, but in this same anxious moment, there has never been a better age for print book lovers.

It was interesting to see how high quality printing of images has been possible for a long time through processes like photogravure and collotype. These are expensive and comparatively fussy processes that have been mostly supplanted (or entirely for collotype) by offset printing, even for high quality reproduction. And with good reason. Quality offset printing is really superb.

The main issue for most publications is, of course, cost. Producing great printing for $100 art books is one thing, but doing it for a $2 magazine is another. Two mass-market publications often praised for their printing quality are Arizona Highways and National Geographic. Arizona Highways prints at 175 lpi using standard offset color. It looks good for a $2 magazine, certainly, though what is a little surprising is that almost any well-produced magazine today looks equally good next to it.

Benson is unabashedly enthusiastic about offset printing, "my trade and my chief love." "Today," he says, "we are witnessing the peak of the process's development. . . . I think it will be around for quite a while yet." While a $2 offset-printed magazine can look quite good, Aperture and some other art-grade periodicals reveal that a $10 offset color journal can achieve near-photo-print quality.

National Geographic has long used 175 lpi (perhaps higher for some plates) six-color rotogravure rather than offset for its editorial well content. Gravure uses regular square cells etched to different depths, each cell being inked to a different depth to describe tones, rather than using dots of varying sizes like offset. This can produce images that look much more like photographic prints. Gravure was the high standard for photo printing in books and journals from the turn of the century though the 1960s. At its apogee, in the hands of the Swiss and French in the 50s and 60s, "the printing is among the very best ever done."

The superlative flat-plate gravure of these old photo books is long gone. National Geographic's modern web-press gravure process is, comparatively, a poor cousin, but at its best is still as good as you can get in a $2 magazine. This expensive process is only cost effective for them because they print six million copies of every issue. Ten years ago that was almost nine million, and with a shrinking subscriber base, it seems their print quality has dropped a bit, too. Issues from the 1990s used a slightly heavier stock and on average exhibited less streaking, skip dot and dirty scrape. Some people attribute this to a change of printer (Quad/Graphics) about ten years ago.

"Despite its complexity," says Benson,"in the end color printing turned out to be easier to do well than black and white." The reasons for this are bit complex and obscure, but basically, color printing "could be done badly and still look good. Even if the print was too heavy, or too light, or somewhat out of balance, the colors' interrelationships could still hold and the colors could be enticing, even if inaccurate. . . . But in black and white work, errors in weight and scale could remove whole areas of content, and tonal distortions could murder the picture."

Just as print starts to fade and ebooks begin to dominate, I find myself becoming increasingly compelled by fine printing. Fortunately, I believe the most aesthetic books with be the last to disappear. They are more than carriers of information and will long have an audience. And on the art side, printed books have never been more beautiful or inexpensive. Print may be tipping into decline, but in this same anxious moment, there has never been a better age for print book lovers.